Introduction

This analysis explores the random variable \( Y = g^U \mod n \), where \( U \) is uniformly distributed over \([1, \text{max\_U}]\). The goal is to observe the shape of the distributions of \( Y \) for various parameters \( n \) and \( g \), and to compute the Shannon entropy of these distributions.

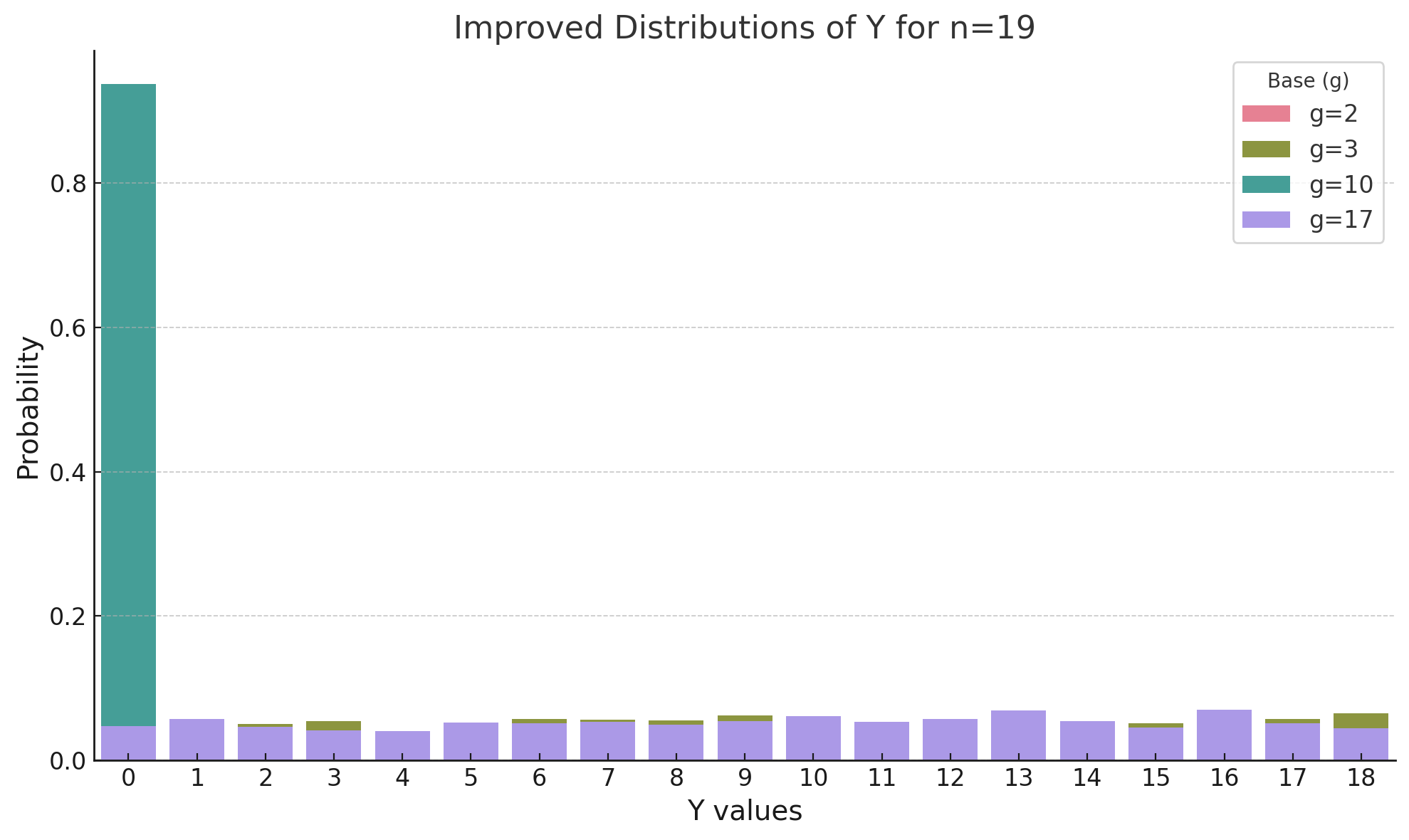

Results for \( n = 19 \)

Below are the distributions of \( Y \) for \( n = 19 \) and different values of \( g \):

- \( g = 2 \): Entropy = 0.601

- \( g = 3 \): Entropy = 4.234

- \( g = 10 \): Entropy = 0.593

- \( g = 17 \): Entropy = 4.233

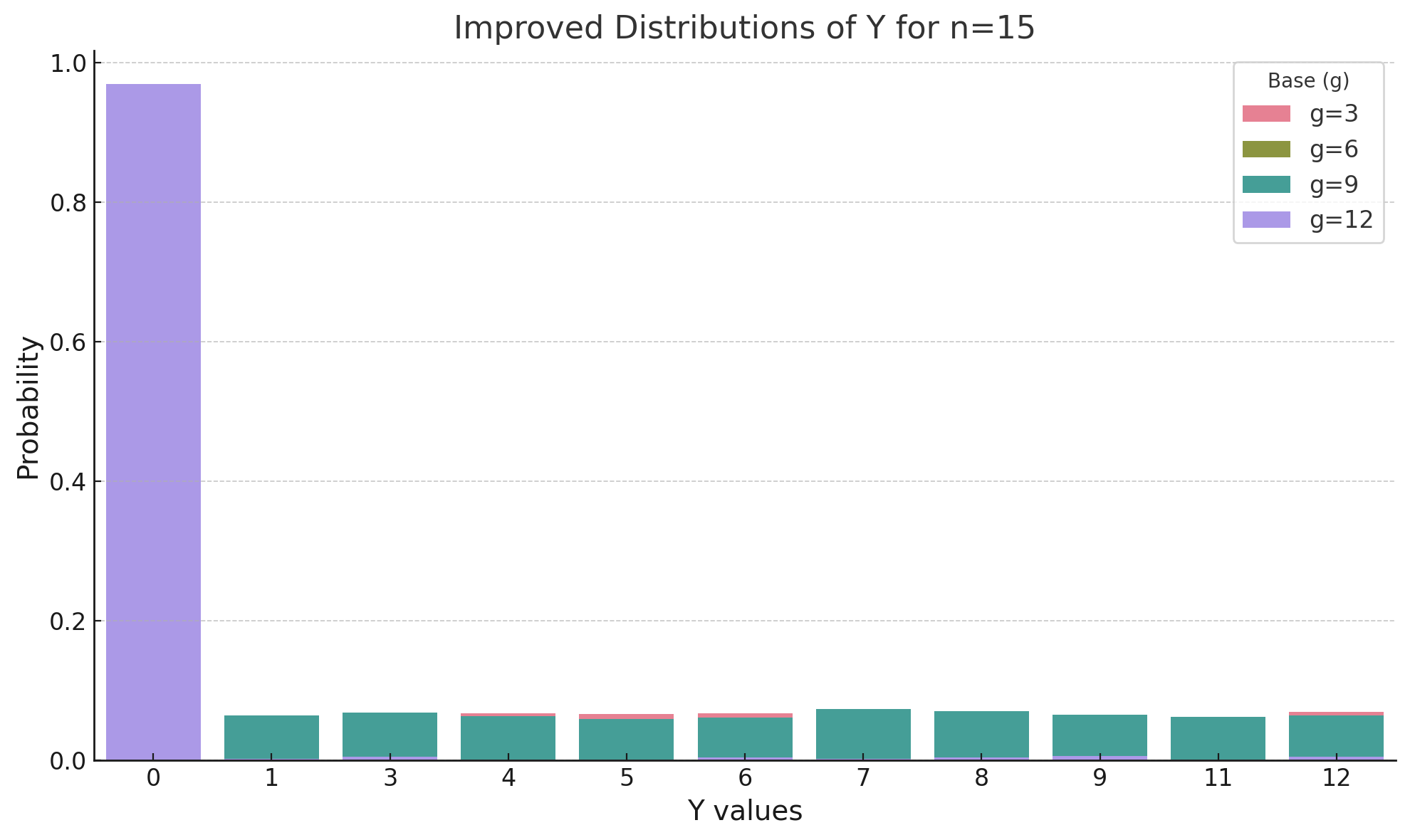

Results for \( n = 15 \)

Below are the distributions of \( Y \) for \( n = 15 \) and different values of \( g \):

- \( g = 3 \): Entropy = 3.903

- \( g = 6 \): Entropy = 0.522

- \( g = 9 \): Entropy = 3.898

- \( g = 12 \): Entropy = 0.294

Observations

The distributions show significant variation depending on the values of \( n \) and \( g \):

- For some values of \( g \), the distributions are uniform, leading to higher entropy.

- For other values of \( g \), the distributions are concentrated on a few values, resulting in lower entropy.

The Shannon entropy highlights the diversity of the distributions. Higher entropy indicates a more uniform distribution, while lower entropy suggests more predictability or concentration in the outcomes.

Implications for Cryptographic Properties

Uniform distributions (e.g., high entropy cases such as \( g = 3 \) for \( n = 19 \)) are desirable for cryptographic applications because they ensure unpredictability. In cryptography, unpredictability minimizes the risk of an attacker deducing the underlying structure or patterns in the data. For example, a uniform distribution of encryption outputs ensures that no particular ciphertext is more likely than another, enhancing security.

Conversely, predictable distributions (e.g., low entropy cases such as \( g = 12 \) for \( n = 15 \)) illustrate potential vulnerabilities. Predictable outputs mean that an attacker could exploit the non-uniformity to narrow down the possible plaintexts or keys, reducing the effective security of the system. Low entropy can also indicate weak key selection, which is a common vulnerability in many cryptographic implementations.

Case A (high entropy) is better suited for cryptographic applications as it maximizes the uncertainty and ensures that each possible output is equally probable. This property is essential for resisting statistical and brute-force attacks. Case B, with lower entropy and higher predictability, demonstrates why careful parameter selection is crucial in cryptographic algorithms. Improper choices can result in skewed distributions, leaving the system open to exploitation.

Why Choose the Set \( \{2, 3, 10, 17\} \) in Case A?

The set \( \{2, 3, 10, 17\} \) is chosen in Case A because these values of \( g \) produce diverse behaviors when used in the computation \( g^U \mod n \). For instance:

- \( g = 2 \): Produces a low entropy distribution with concentrated probabilities.

- \( g = 3 \): Generates a nearly uniform distribution, ideal for cryptographic applications.

- \( g = 10 \): Similar to \( g = 2 \), creates a distribution with significant concentration on certain values.

- \( g = 17 \): Like \( g = 3 \), results in a high entropy and uniform distribution.

These specific values were likely selected to showcase both high-entropy and low-entropy scenarios, highlighting their implications for cryptographic security. By including both types of behavior, the exercise emphasizes the importance of selecting appropriate parameters for cryptographic algorithms.

Spotting Possible Errors in the Exercise

While the exercise provides valuable insights, potential issues include:

- The range of \( U \) (\([1, \text{max\_U}])\) might not be representative of real-world cryptographic scenarios. Larger ranges could better demonstrate uniformity.

- The choice of \( n \) and \( g \) may inadvertently introduce biases that are not explicitly discussed. For example, small values of \( n \) might limit the diversity of possible outputs.

- It assumes that the results are directly applicable to cryptographic systems, but real-world cryptography involves additional complexities such as key management and randomness sources.